Just before Halloween as I do every year, I visited Willard Pond in Hancock. It’s about as close to a wilderness as you can come these days, at least in this area, and it’s very beautiful. Even the road in was amazing.

Unless you have time to go to a place each day to watch the turning of the leaves you can only go by experience, which in this case means what you’ve seen in the past. In the past I’ve always found the oaks and beeches in this forest at their peak during Halloween week, but there were a lot of bare trees over there. But no matter; I knew it would be beautiful. We’re going to walk right along the shore of that hillside.

It was a windy day and the wind turbines that just peek up over one of the hills were spinning faster than I’ve ever seen. I remember being shocked by their size the first time I saw them.

Though I don’t remember if this photo shows the start of the trail, it does show what the trail typically looks like. It follows along very close to the water and in many places it’s one person wide.

Since you have the hill on your left and the water on your right on the way in, it’s virtually impossible to get lost, but just in case the trees are well blazed. By the way, it’s a good idea to know what trail blazes mean and how they’re used.

From here on it is total immersion in a kaleidoscope of color and beauty. There’s nothing quite like a hardwood forest in the fall; some of the most beautiful fall foliage I’ve seen has been seen right here.

Small maples that had been cut along the trail had grown back, and they were beautifully red.

But most of the maple leaves had found their way into the water of the pond.

There are several places where small streams come down off the hillside to the pond but there are boardwalks in place. Still, wearing good waterproof hiking boots here is a good idea.

Maple leaf viburnums (Viburnum acerifolium) were beautiful as always in reds and pinks but they were also untouched by insects, which is unusual.

Big, hand sized hobblebush leaves (Viburnum lantanoides) weren’t quite so pristine but they were still beautiful. I noticed that all their fruit had been eaten already.

The hobblebushes had their buds all ready for spring. These are naked buds with no bud scales. Instead their hairs protect them. The part that looks swollen is a flower bud and come May, it will be beautiful.

As is always the case when I come here, I couldn’t stop taking photos of the amazing trees. It’s hard to describe what a beautiful place this is, so I’ll let the photos do the talking.

There was a large colony of corydalis growing on a boulder and if I had to guess I’d say it was the pink corydalis (Corydalis sempervirens,) also known as rock harlequin. That plant blooms in summer and has pretty pink and yellow blooms but since I’ve only been here in the fall, I’ve never seen them in bloom. Next summer though, I’ll have a lot more free time and I’d love to visit this place in all four seasons.

A tiny polypody fern (Polypodium virginianum) was just getting started on another boulder. Polypody fern is also called the rock cap fern, for good reason. Though I’ve seen them growing on the ground once or twice there must have been a rock buried where they grew, because they love growing on stone. They are evergreen and very tough, and can be found all winter long.

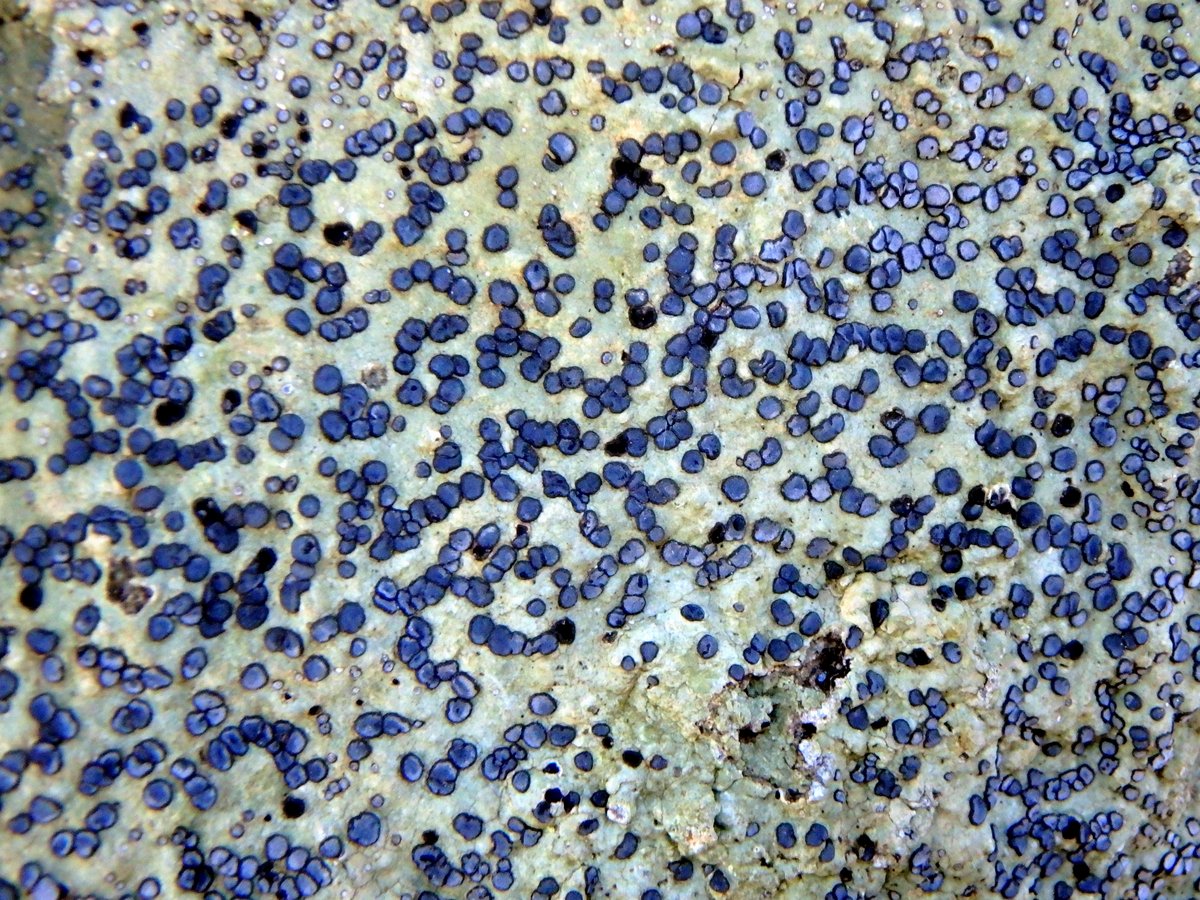

There are plenty of boulders for rock loving plants to grow on and this is one of the largest I’ve ever seen. Easily as big as a garage, the black coloring on it and other boulders comes from the spore bearing surface of rock tripe lichens (Umbilicaria mammulata,) which grow here by the many thousands. Rock tripe is edible but I imagine they must taste like old rubber. Still, they were a source of emergency food for Native Americans and saved the lives of many an early settler. Even George Washington’s troops are said to have eaten rock tripe to survive the brutal winter at Valley Forge in 1777.

A beaver once gnawed on this huge old yellow birch and it was in the process of healing itself, which is something I’ve never seen a tree this old do. The will to live is very strong in all living things, and this is a great example of that. Though I didn’t see them in person I see some polypody ferns growing at the base of it in this photo. Whether on an unseen stone or on the tree itself, I don’t know.

Something else I’ve never seen is target canker on a yellow birch, but here it was. Target canker doesn’t harm the tree but causes its bark to grow in circular patterns of narrow plates which helps protect it from the canker. According to Cornell university: “A fungus invades healthy bark, killing it. During the following growing season, the tree responds with a new layer of bark and undifferentiated wood (callus) to contain the pathogen. However, in the next dormant season the pathogen breaches that barrier and kills additional bark. Over the years, this seasonal alternation of pathogen invasion and host defense response leads to development of a ‘canker’ with concentric ridges of callus tissue—a ‘target canker.’” Apparently, the fungal attacker gives up after a while, because as the tree ages the patterns disappear and the tree seems fine. What interests me most about this is how I’ve read that target canker is only supposed to appear on red maples. Now I can no longer say that is true.

A common earth ball (Scleroderma citrinum) grew beside the trail and looked as if it was nearly ready to release its spores. Another name for it is the pigskin puffball and it is toxic. It likes to grow on compacted soil like that found on forest trails. They often have a yellow color on their surface and are also called citrine earth balls because of it. I’ve seen them with a beautiful lemon-yellow color.

My grandmother was with me in spirit when I found a berry on an American wintergreen plant (Gaultheria procumbens,) which she always called checkerberry. It was the ffirst plant she ever taught me and we used to go looking for the minty tasting berries together. It is also called teaberry because the leaves were once used as a tea substitute.

The big leaves of striped maple (Acer pensylvanicum) had taken on their yellow fall color. They’ll lighten to almost white before they drop.

I saw many things here I’ve never seen before on this day, and one of them was the seeds (samaras) of striped maple. I’ve seen thousands of these trees but this is the first time I’ve ever seen the seeds.

Witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana) grows in abundance all along the trail. Though I’ve seen them blooming profusely here, on this day these were the only blossoms I saw.

This little wooden bench is usually as far as I go for two reasons; because by the time I reach this spot I’ve usually taken far more photos than I can ever use, and because I like to sit in this quiet place and enjoy the serenity and splendor of nature. It just doesn’t get a lot better than this, in my opinion.

As I sat on the bench I watched the ripples for a while as they flowed over the still fresh and beautiful leaves on the bottom of the pond. I could hear a loon calling off on the far shore and I wasn’t surprised. I hear them almost every time I come here but I’ve never seen one. Probably just as well, because they’re an endangered bird. They die from eating lead fishing weights, and that is why only fly fishing is allowed here.

Sometimes when I sit on the bench I watch the water, and sometimes I turn around to see the colors. One is just as beautiful as the other but colors like these can’t be seen year-round.

As I got back on the trail to leave a chipmunk ran up a tree root and stared, as if to ask why I was leaving so soon. Though it had seemed like hardly any time at all, I had been here three hours. I hope all of you have beautiful woodland places to visit. They’re very uplifting.

If you are lost inside the beauties of nature, do not try to be found. ~Mehmet Murat ildan

Thanks for stopping in.