This post is kind of a continuation of the last. I’m still spending time walking through what is really a huge wetland area, and of course I’m seeing many things which like that kind of environment. This particular visit started off quite foggy, but this photo was taken just as the fog began to break. You can still see it; gray and soft off in the distance.

These weren’t raindrops; they were condensed fog drops. It was that kind of morning.

This place is a place of water drainage and every now and then all that water drains into a low spot and becomes a pond, and they are always full of life. I’ve seen beavers, snapping turtles, great blue herons, and too many smaller birds to name here. Right now the yellow bullhead pond lilies are blooming and for the first time I’ve seen a strange thing happenig; some type of bird flies down and lands on a leaf and then hops from leaf to leaf. I think the birds that do this are red winged blackbirds but I can’t be sure yet. Whatever the birds are, they must be looking for insects.

One of the smaller birds I met at the pond was a Kingbird, which is an amazing acrobat. It is one of the flycatcher clan. It would find a good perch and sit for a bit and then it would be off, swooping high and low and left and right before coming back to the same perch, much like a dragonfly would. That means it’s easy to anticipate where it will land and get set up for a shot of it but even so, without a tripod this was the best I could do. According to what I’ve read Kingbirds get their name from how aggressively they defend their territory, even against hawks. They are king of the hill in birdville and they have no fear of anything, humans included. Its scientific name Tyrannus tyrannus even hints at it being a bit of a tyrant, but they landed and perched near me many times as if I wasn’t even there. I watched this one catch dragonflies in mid air, which it once did so close to me I could have touched it.

Out went the wings, up came the feet and like a rocket this bird was gone so fast I didn’t even know it had left. This shot was taken purely by accident; when I clicked the shutter I think the bird was still sitting on the branch. Since plants don’t fly away I don’t need stop action camera settings so it’s just a blur. Luckily I’m not out to win any photography awards; I’m just here to show you the beauty of nature and this shot, even though blurry, shows you something not often seen. Between my old beater camera that I’ve fallen on too many times to count and my cataract dimmed eyes I’m lucky to be able to post any photos at all, so I can’t complain.

I was happy to find the oval leaves of floating pond weed floating just off shore. That meant that, though I couldn’t reach them, I could get a close look at the plant’s small, cigar shaped flower heads.

This is a better shot than I’ve ever gotten from a wave rocked kayak. I think you can just get a side glimpse of a couple of the tiny white flowers toward the top, but the rest had all gone to seed already. At least, that’s what I think this shows. If nothing else it shows the seed head, which is something you don’t see every day. Another thing you don’t see is the plant’s second set of leaves, which are grass like and stay underwater.

I was leaving the pond when this cute little thing flew past and landed on this leaf in front of me, just as you see it here. It was if it was saying “I’m ready for my photo shoot,” so here it is. Google lens says it’s a common ringlet butterfly. I looked at other examples online and it seems to be a match. I’m not sure that I’ve ever seen one before; at first I thought it was a cabbage white but once I saw it on the computer I saw that there really wasn’t a lot of white on it.

For a long time I had read and heard about the wonderful scent of our beautiful fragrant white water lily but since they were always offshore just out of reach, I doubted I’d ever smell them. After all, how can you smell a flower you can’t get near? I had given up the thought of ever smelling them until one day a few years ago I walked around a pond with hundreds of them growing in it, looking for that perfect photo, when a breeze blew across the pond. Here was the delicate, fruity scent of hundreds of these beautiful flowers, as light as the breeze that carried it, and it was wonderful.

George Washington loved orchard grass because, he said: “Orchard grass of all others is in my opinion the best mixture with clover; it blooms precisely at the same time, rises quick again after cutting, stands thick, yields well, and both cattle and horses are fond of it green or in hay.” I like it because of its simple beauty. It will slowly turn purple as it ripens and become even more beautiful.

Nature is always full of surprises; that’s one thing you can count on. How, I wondered, could I have spent the better part of 60+ years outside, and even walked by this very spot for at least two decades and not seen this grass? It’s all about being in the right place at the right time, and apparently I’ve just never been here when this grass was flowering. It is called June grass, and it’s beautiful. If nothing else this illustrates why it’s a good idea to walk the same places again and again. Nature is in a state of constant change so you can’t expect to walk a trail once and think you’ve seen all there is to see.

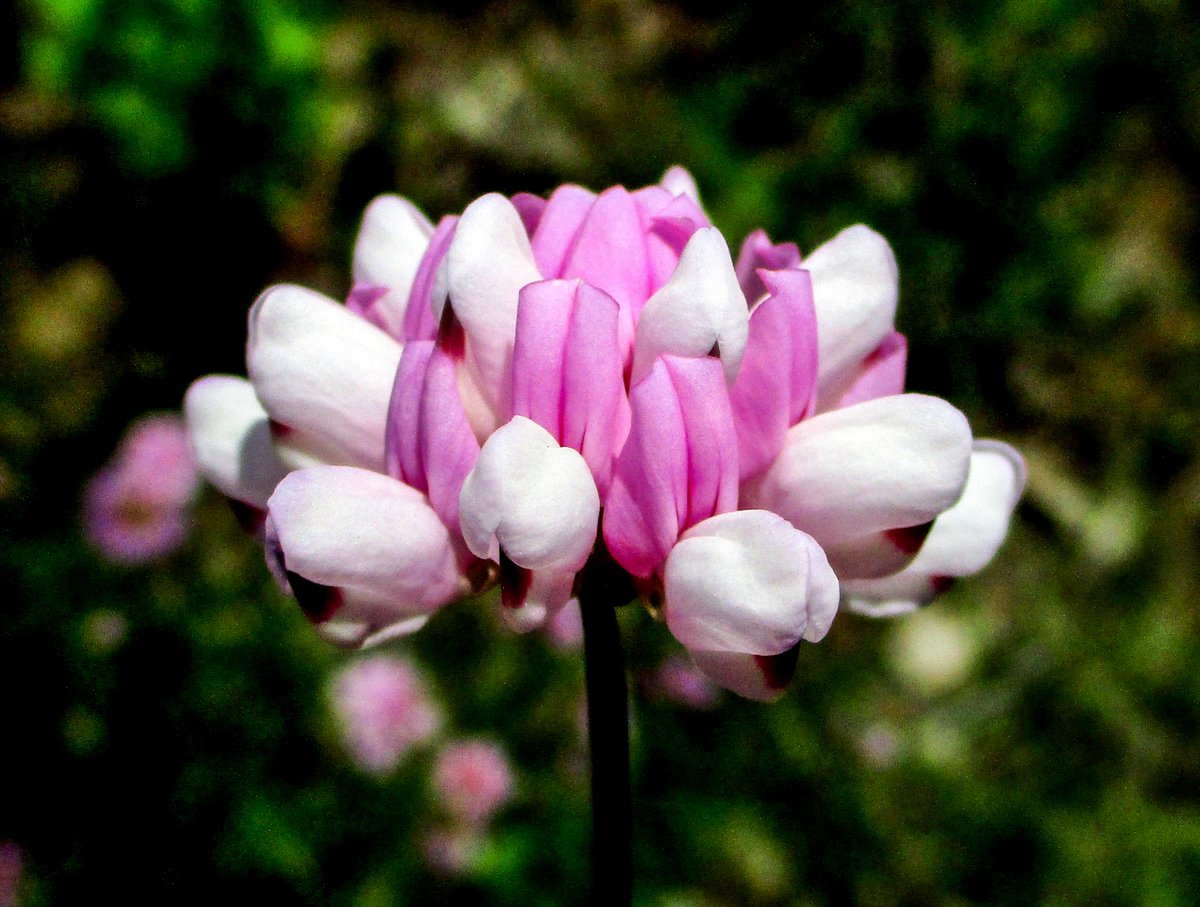

I’ve wondered for a long time if I was seeing sheep laurel or bog laurel. The keys to identification I read weren’t really clear, and to make matters worse sheep laurel is able to grow in bogs, and bog laurel can grow on dry land. But then I found clarity: sheep laurel leaves have a stem, called a petiole, which attaches them to the main stem. Also, 3 leaves usually form a whorl around them stem. Bog laurel leaves have no leaf stem; they are sessile on the main stem and two leaves grow opposite each other. Sessile means no petiole or leaf stem. So, all of that is a long winded way to say the beautiful flowers in this shot belong to sheep laurel.

Thanks to the Maine Natural History Observatory for clearing that up.

This little mother wood duck seems to be wearing a joyful expression but the actual moment was quite different. I was walking a trail around a pond when she came gliding out of the woods and landed off shore. Then she swam in circles, whistling and hooting loudly, as if frightened. Soon I saw why; 7 or 8 little ducklings swam out from some pickerel weeds very near where I had just been walking. I walked right by them without seeing them and wouldn’t have done more than take a photo if I had, but their mother didn’t know that and she was about as agitated as a bird could be. They all swam off while I stood there watching, and it happened so fast I never did get a good shot of the ducklings.

Female wood ducks don’t quack; they kind of whistle or squeak with an urgent sound that’s very hard, if not impossible to describe. It’s also one of those sounds that, once heard you don’t forget. It’s easily found online if you’re interested.

I was thinking as I looked at this shot of a tachinid fly how, if I had taken it in a cemetery I could have said “fly on the family stone” but since it wasn’t, I won’t. It landed on a stone in a stone wall and walked around in circles as if looking for something. It might have been on the trail of a caterpillar, because they lay eggs on young caterpillars. The eggs hatch and the fly larvae begin to drink the “blood” of the caterpillar. That means the caterpillar won’t go on to become what it should have. Some call this fly the enemy of butterflies for that reason but I see it simply doing what it has evolved to do. That’s what it does and it really doesn’t matter what we think about it; nature doesn’t know or care about good or bad.

I saw another large clump of yellow irises along the river bank, so this makes two now in this general area. This is an iris from Europe that is quite aggressive. I found a small pond once that was absolutely choked with them so there wasn’t even room for cattails to grow there. I’m not sure what the plants get out of growing so thickly that they starve themselves enough to stop flowering, but that seems to be what they do.

But there is no denying the unique beauty of this iris. The featureless background in this shot is the river itself, but it looks like I was holding a gray card behind the flower. I’ve never seen this happen but we’ve had some strange light, what with smoke from wildfires and lots of clouds, so I was happy to get a shot at all.

Maiden pinks can now be seen blooming just about everywhere, usually in the color seen above or in white. Originally from Europe, they escaped cultivation almost immediately but they aren’t terribly invasive. They like dry, hot, sandy soil in waste places and that’s where I find them. The name “pinks” is supposed to come from pinking shears, which leave a serrated cut in cloth that is similar to what is seen on its petals, but since the flowers must have come along much earlier than the shears, I question that theory.

But anyhow, if you like them there are garden cultivars sold under the name “pinks” which can be found at any nursery. One old red flowered variety is called “flashing lights.” It’s a name I’ve always thought was appropriate for these little flowers. I see them flashing just about everywhere I go.

Orange isn’t a common color in nature where I live so it’s always nice to see orange hawkweed coming into bloom. It isn’t anywhere near as common as yellow hawkweed but I’ve seen it a few times lately.

The flowers of this plant grow on long thin stems (pedicels) and dance in the slightest hint of a breeze, and for that reason it was named fawn’s breath. Native Americans used the powdered root as a laxative and for that reason it is also called American ipecac. That takes a bit of the sweetness away from the name fawn’s breath, but that’s the way it is. It’s a beautiful thing unless you eat it, then any thoughts of beauty might just go down the drain.

A pretty, native wild honeysuckle that blooms after all the invasive honeysuckles have finished is glaucous honeysuckle. It is also called limber honeysuckle and I can understand why, because its long branches are so limber they flop on the ground rather than stand up. “Glaucous” means blue green in color, or covered by the natural, powdery bluish wax called “bloom.” The leaves are bluish green and the stems have the same bluish powdery bloom that blueberries have, so the name fits perfectly. It likes well drained, constantly moist soil and I find it growing in gravel at the base of a small hill. This plant is the only one I’ve ever found.

The pretty flowers of glaucous honeysuckle shout honeysuckle. I haven’t seen a true native honeysuckle flower yet that didn’t have that big red, mushroom headed pistil, and here it is on these flowers. What beautiful color both the flowers and flower buds have.

Every time I see Canada anemones bloom I think back to a woman who had just bought a house and had heard about me from others in the neighborhood and wanted to meet me. As we stood in her yard one day talking and planning she made it clear that if I were to be her gardener under no circumstances would I plant anemones. Of course I had to ask about the white flowers we stood beside which were in fact anemones, but they didn’t bother her. Though I worked for her for many years I never did find out why anemones bothered her, or even which anemones she was thinking of. Since she had been in the foreign service and had lived all over the world, they could have been anything.

Called one of the most invasive weeds worldwide, creeping thistle plants are shoots that grow from an extensive network of long, thick, underground roots. Trying to pull the plants just breaks them off the underground root and new plants soon take their place. Mowing all the above ground growth just makes the roots spread more, and they can spread as much as 10 feet in a season. The plant is originally from Europe but is also called Canada thistle. Its leaves have sharp spines all along the edges so just holding on to them on a windy day to get a photo is a challenge. I’ve taken photos of its flowers for years but this year I noticed how beautiful its buds were. As pretty as it is though, you don’t want this one growing in your yard.

I hadn’t seen any caterpillars yet so from a distance I was surprised to see what I thought were tent caterpillars swarming all over a stick. When I got closer I saw that it was instead a dead weed. But what a beautiful weed. I called it Rapunzel. It reminded me once again how there is beauty everywhere you care to look on this earth. Climb a hill, step behind a tree, dig a hole or roll over a log; no matter what you do or where you do it you will surely find beauty there.

To illustrate what I said about beauty being everywhere; I happened upon a spot where someone had lifted a log from the forest floor and revealed this bright orange mushroom mycelium that had been growing under it. I thought it was a very beautiful color, and so unexpected it stopped me in my tracks. It helps I think, to know that much of the beauty of life is found in small, seemingly insignificant things that might appear at any moment as you move slowly through nature. Even a pebble can sometimes be as beautiful as a jewel, so don’t just look; open your mind and heart and really see. Perceive the beauty of life using all of your senses. These wonders are all around us. It’s all there, just waiting for us to find it.

Green was the silence, wet was the light;

the month of June trembled like a butterfly.

~Pablo Neruda

Thanks for coming by.