I started these “things I’ve seen posts” years ago because I had lots of photos that just didn’t seem to fit in other posts. I think this is the first one I’ve done this year but these are all recent photos that also didn’t fit in, like this milkweed seed resting on a branch that I saw just the other day. It was most likely taken by the wind not too long after I’d left. According to the University of Maine Native American used milkweed as medicine to treat a variety of ailments, made the stem fibers into yarn, and ate the plant as well, ingesting the young shoots, flowers, and young green fruits of milkweed. The shoots have been compared to asparagus and the unopened buds to broccoli.

Since the corn fields near here began to flood the farmer started planting wheat, so I thought these plants I found growing under the powerlines nearby were wheat escapees but Canada wild rye, native to the great plains, looks very similar after the leaves have died back. Wild rye seeds are edible and were used as food by Native Americans.

I also found some Canada lily seed pods under the powerlines. They had opened and were releasing seeds. They split into three sections when they open, and each section has two rounded lobes which the seeds fit into perfectly.

Looking at the seeds it’s easy to see how the rounded parts fit into the rounded lobes in each section of seed pod. The pointed part points toward the center of the pod and the flat seeds are stacked into each lobe, meaning that each seed pod carries many seeds. Canada lily bulbs are edible but they were a famine food, used by Native Americans only when other foods weren’t available. When roasted they are said to taste like an ear of unripe corn. The seeds remind me of American elm seeds.

I like to see the beautiful blue of juniper berries but they don’t last long because bluebirds and other birds eat them up as fast as they ripen. A waxy coating reflects the light in a way that makes the deep purple black berries appear to be a bright and beautiful blue. Though called a berry botanically speaking the fruit is actually a seed cone with fleshy, merged scales. The flavor of gin comes from the juniper plant’s unripe berry and the ripe berry is the only part of a conifer known to be used as a spice. Whole and / or ground fruit is used on game like venison, moose, and bear meat. The first recorded usage of juniper appears on an Egyptian papyrus from 1500 BC. Egyptians used juniper medicinally and Native Americans used the fruit as both food and medicine. Stomach disorders, infections and arthritis were among the ailments treated. Natives also made jewelry from the seeds inside the berries, which I keep telling myself I’ll look at but never do.

A dead Queen Anne’s lace flower head looked like a starburst in the bright sunlight.

I went to the river several times this past summer to see the beautiful iridescent colors of mussel shells. There was no question that they would be there because raccoons go there to fish and when they’re done eating the meat of the mussel they leave the shells behind. But this year every time I went to see them the shells were broken into pieces. Who or what was breaking them? They’ve never been broken in past years and I can’t imagine an animal doing it. I’ve noticed footprints in the sand now and then though, so I have an idea that it might be the work of a someone rather than a something. Too bad; if they stopped for a moment to see how the light brought out the beautiful colors of the shells maybe they’d see what they had been depriving themselves of by breaking them.

I found a great illustration of a branch collar. The dark part sticking up is obviously the dead branch but what is maybe no so obvious is the branch collar below it, which is shaped like a volcano. When pruning trees it is always best to cut the branch and leave the branch collar intact because this exposes less of the tree’s surface area to insects and fungal spores. It’s easy to see the difference between the diameter of the branch compared to the base of the branch collar.

I went out one cold night to get something out of the car and saw this half moon shining brightly so I went back in and got the camera, steadied it on a post and took this shot. It would have been better if I had used a tripod. I remember as a boy in 1969 I used my father’s binoculars to see if I could see the Lunar Orbiter circling the moon, but I never did see it. The thought of people actually up there walking on the moon was awe inspiring. Everything stopped as the people of earth (650 million) watched the lunar landing on television. We all came together as one people then, and it seemed such a great time to be alive.

Two mallards swam blue streaks across a golden pond. This photo is right from the camera just as it happened, without any re-touching. I’ve seen golden water and I’ve seen blue water, but I’ve never seen this. Of course it’s all about the light; it is the light that makes things beautiful. Ponds are starting to ice over, so mallards and geese will have a harder time finding open water soon.

Long, faceted spears of ice formed along the shore of another pond. They were barely noticeable unless the light fell on them in a certain way, so it took a few tries to get a shot of them.

There were a few ice baubles along the river shore on this day. It has to get quite cold for them to form. It seems to take at least a couple of nights in the 20s F. to get them started.

On another day many ice baubles were catching the bright sunlight beautifully and acting like prisms with colors both in them and shining out of them but try as I might, I couldn’t catch them in the camera. I was finally able to get the blue of the sky reflected in this one though. I wanted to try a cellphone camera but the rocks on shore were covered in ice and I would have had to kneel on them while I held the phone out over the water. It didn’t seem like a very good plan.

This was a strange, hand shaped ice bauble. The wind howls up and down the river at times so I can only guess that the wind was the sculptor. It must have been a very cold and windy night. The sun’s light was again beautifully colored by it but again, I couldn’t catch it so I’ll have to keep trying. Quite often you find that the camera can’t see what your eyes can.

Hoar frost covered much of the grass on the riverbank.

From what I’ve read, hoar frost is a type of feathery frost that forms by condensation of water vapor to ice at temperatures below freezing. The word ‘hoar’ comes from old English and refers to the old age appearance of the frost: the way the ice crystals form makes it look like white hair or a beard. One of the best places to find hoarfrost is on exposed plants near unfrozen lakes and streams. There are times when you can walk along a stream and see all the stream side shrubs covered with it.

Since it was cold enough I went to the outflow of Swanzey Lake. The small waterfall there always makes good splash ice at this time of year.

Though I’m not sure why, splash ice is usually more opaque than the ice baubles along the river that are made by waves washing over a twig or plant stem. It’s never as clear, but it is just as interesting. If I had to guess I’d say the whitish color is due to large concentrations of oxygen, much like white puddle ice is.

The ice that grew on a big boulder looked like what I imagine the barnacles on a ship’s hull would look like.

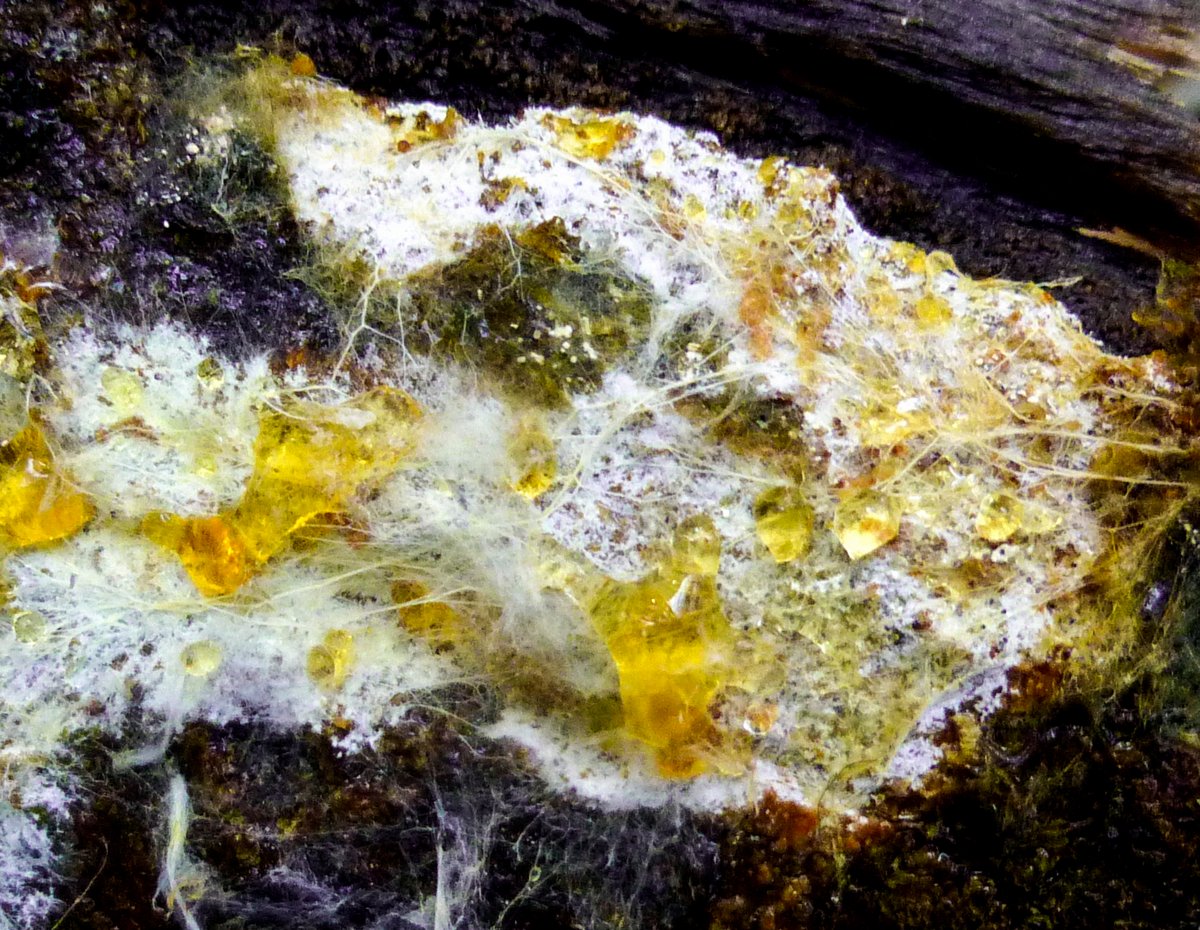

I had forgotten about the iron rich seep in this place. Seeps don’t flow; they just sit on the surface like a puddle. I know of some that have been where they are for many years, but none I’ve seen are as richly colored as this one. The water in a seep reaches the earth’s surface from an underground aquifer and apparently stays somewhat warm, because I’ve never seen a seep freeze over. In a way though I wish they would; I’d like to see red puddle ice.

Another small pond had mostly frozen over but the ice was thin. A goose landing on it would have probably broken through but geese swim in the river at this time of year, where it takes longer for ice to form.

A fragrant white waterlily leaf had been caught in the ice. In summer the surface this pond is covered by many hundreds of them. Pond and lake ice always looks perfectly smooth but it rarely is because the wind sculpts and forms it.

I don’t see sun dogs often but last Saturday afternoon I saw what looked almost like a vertical rainbow to the right of the sun. Sundogs happen when there are ice crystals in the atmosphere. The ice crystals act much like prisms and color the light, which is often red closest to the sun, yellow in the center and white at the farthest edge. I could see two sundogs, one on either side of the sun, and an arc or “bow” overhead, but I couldn’t get far enough away to get them all in one photo. The scene covered a huge area.

I found this photo of sundogs on Wikipedia. It was taken in Saskatoon, Canada by Carlos Enrique Díaz Fecha last year. If I had been far enough away I could have gotten a shot much like this one, but I could only get the sundog on the right side of the sun. As I drove under the arc I watched the one on the left, hoping for a good place to stop but I never did find one; I was just too close. Sundogs get their name from the way they follow or “dog” the sun. This isn’t new; Aristotle (384-322 BC) once noted that “two mock suns rose with the sun and followed it all through the day until sunset.” He said that “mock suns” are always to the side, never above or below, most commonly at sunrise or sunset, and more rarely in the middle of the day.

I zoomed in a little closer, thinking I’d see something different but I didn’t. Just color; an amplification and bending of the light. Though sundogs warn of coming storms it was nice to see them; an interesting and beautiful end to the day.

It’s not what you look at that matters, it’s what you see. ~Henry David Thoreau

Thanks for coming by.