It has been nearly a year since I last visited the man-made canyon on the deep cut rail trail up in Westmoreland, because the last time I visited there had been a rockslide in the southern end of the man-made canyon and it had flooded the canyon badly. The northern canyon seen here remained mostly untouched.

I say mostly untouched because rock falls were also happening in the northern canyon. If you look closely up ahead on the right side you can see a caution sign, there so snowmobiles don’t crash into the rock fall in winter.

The largest stone seen here is about half the size of a Volkswagen beetle, and it surely would have crushed one if one had been there when it fell.

Above the rock fall is a scary scene, because huge stones have detached from the wall and are ready to fall. You can see marks from the old steam drills and the stone has come loose from the face of the canyon along the line of one of the drill marks. This is a dangerous situation that I will stay away from until that loose, car crushing stone has fallen.

The reason so many stones fall is because there is a lot of groundwater here. The water seeps into any crack in the stone and when it gets cold enough it freezes and expands, and ever so slowly the stones are pushed apart. Eventually they fall, but this never would have happened when the trains were running because the railroad would have regularly inspected the route.

Though some features, like that beautifully built retaining wall on the left, need little maintenance the drainage channels that run through here need regular cleaning of leaves, silt and branches or they dam themselves up and flood into the trail. This has happened in several spots along this section of trail. There is a lot of water here and if it doesn’t have a way to run off, it causes problems.

The reason I started regularly coming to this place is because I found plants here that I couldn’t find anywhere else, like the wild chervil seen in the photo above. Its leaves were still nice and green and I think that was because there hadn’t been a frost here yet. This place has its own weather and usually runs about 10 degrees cooler, but on this day it was warm and so humid the camera lens kept fogging up. I was also swatting mosquitoes in November, which was a first. Wild chervil isn’t the same as the cultivated chervil used to flavor soups so it should never be eaten. In many places it is called cow parsley and it closely resembles many plants like water hemlock that are extremely poisonous. It’s a good plant to admire and just leave alone.

I saw some late fall oyster mushrooms on a log. On this side they had just appeared and were whitish colored…

…and on the other side of the log they had some age and had darkened. These mushrooms almost always form in overlapping groups. They are sometimes said to be the last mushroom seen before winter but there are many others that fruit in late fall. Though I didn’t show them here the gills are yellow to yellow orange. When quite young they also have a yellowish color where the cap meets the stem and that is the “glow” seen in the previous photo.

There are lots of ferns here, including the evergreen wood ferns seen here. These ferns are true evergreens, holding on to their green fronds under the snow until spring.

If you’re interested in knowing what fern it is you happen to be seeing a good guide book is Identifying Ferns the Easy Way: A Pocket Guide to Common Ferns of the Northeast by Lynn Levine. When I bought it, it was $10.95, which is a low price for a guide as good as this one. One of the things she explains in detail is how to use a fern’s spore case locality on the leaf to identify it.

On another log there were some brown cup fungi growing on a log and they must have been tasty because something, probably a squirrel or chipmunk, had been nibbling at them. According to Michael Kuo at Mushroom Expert. Com these are among the most difficult fungi to identify. I call them brown cup fungi because they are brown and cup shaped but they could be one of several different species.

I looked up to the rim of the canyon and there was a young beech so bright against the background trees it looked to be on fire. Though the walls of the canyon look barren at this time of year in summer they are lush and green, with masses of violets and other flowers growing anywhere they can get a foothold. It transforms itself into a beautiful Shangri-La.

One of the most unusual things I’ve found growing on these walls is algae. Even though what you see is colored carrot orange it is called green algae. Over about a dozen years it has grown to about twice the size it was when I first found it and has even started growing on the opposite wall of the canyon. I keep hoping I’ll see it producing spores but I haven’t yet.

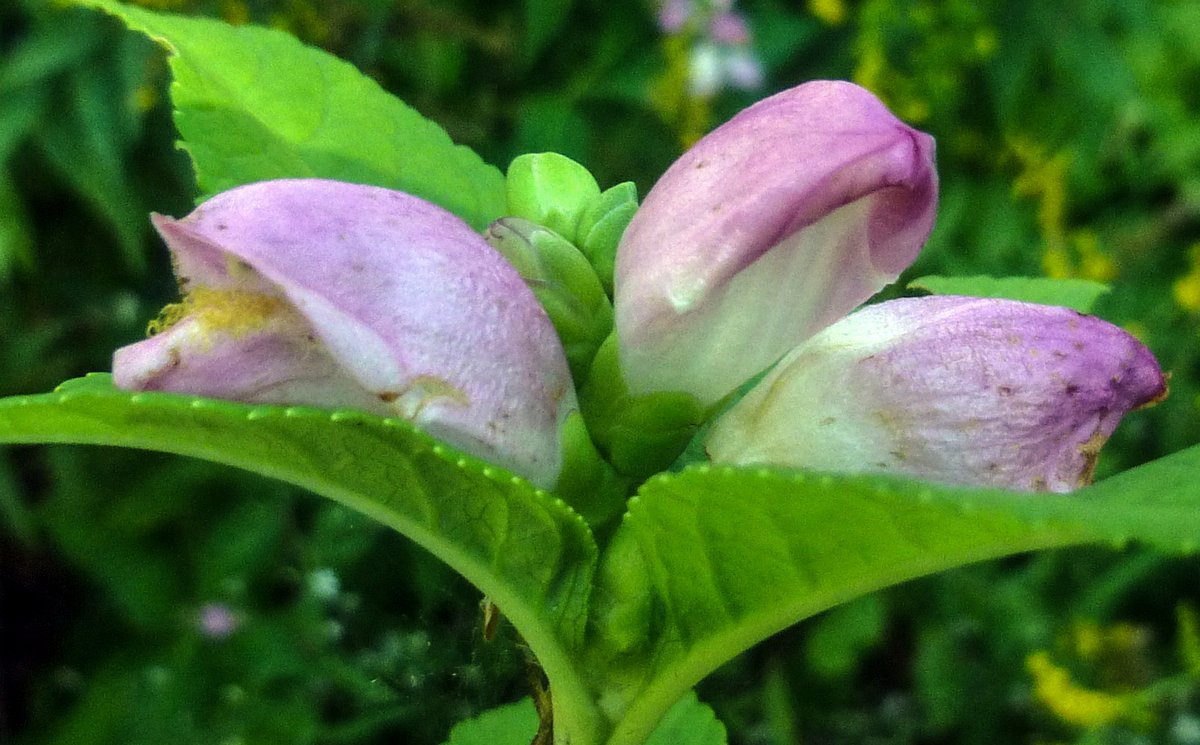

I found lots of beech drops here. They grow near beech trees and are a parasite that fasten onto the roots of the tree using root like structures. They take all of their nutrients from the tree so they don’t need leaves, chlorophyll, or sunlight. Beech drops are annuals that die off in cold weather, but they can often be found growing in the same place each year.

Tiny pinkish purple flowers with a darker purplish or reddish stripe are the only things found on a beech drop’s leafless stems. On the lower part of the stem are flowers that never have to open because they self-fertilize. They are known as cleistogamous flowers. On the upper part of the stem are tubular flowers which open and are pollinated by insects. The flowers seen here never really opened, possibly because it is so late in the season. I usually find them blossoming in September.

I was surprised to find leaves on this young maple. I think it was an invasive Norway maple, which hold their leaves until most other maples have dropped theirs. Their fall color is yellow as well. The real test is to break a leaf stem. If it has white latex rather than clear sap it is a Norway maple.

These leaves had a good case of powdery mildew. Like tar spot, which is another leaf attacking disease, it is unsightly but it doesn’t harm the health of the tree.

Since I knew how wet the trail ahead was, and since I wasn’t going “thru,” I skirted the sign so I could see what had been done over the summer.

The answer was, not much. They had broken up the huge stone slab that had slipped off the hillside though, so that was a start. I had spoken to one of the people who were going to do the work so I know there are big plans for the place. I’m guessing they’re waiting for the ground to freeze so the heavy equipment doesn’t destroy what is left of the trail. In this photo you can see by the stone standing upright how thick the slab was. When it slipped it came to rest in the drainage channel, plugging it tight and flooding the trail.

There were three of these huge slabs of rock along this section of trail and now there are two. If the others let go and slide into the trail I hope I’m not here when it happens. This shot of one of the two slabs still left gives you an idea of how big they are. You could park a Volkswagen beetle on this one. In winter they are covered in sheets of ice about 6 inches think, and I always hoped the ice wouldn’t give way when I was here in the winter. That the stone would let go and slip never crossed my mind. It must have made quite a rumbling sound.

This view gives an idea of how thick the slabs are; I’d guess about 18 inches. The slab of rock that fell was about the same thickness as what is seen here but it was bigger, if I remember correctly. It was also covered in ice when it fell. The green you see here and there in this shot are great scented liverworts. There was a lot of water between us so I couldn’t get any closer.

For the first time since I’ve been coming here I found great scented liverwort growing in soil beside the trail. I’ve always liked its reptilian appearance and its clean, fresh scent. I hope it continues to grow in this spot but it is a very fussy plant that will refuse to grow if the conditions aren’t right. It demands clean, unpolluted water, for instance.

Also for the first time, I saw a yellow jelly fungus growing on a leaf. Or it might have grown through holes in this beech leaf. I’ve never seen them grow on anything but wood. There is always something unusual to see, every time I come here.

I had to reach out and run my hand over this white tipped Hedwigia moss. It seems more animal than plant and it begs to be petted. When it looks like it does in this photo it is at its optimum; it has had plenty of water and is good and healthy, and is at the top of its game. When dry it looks completely different. The white tips are caused by young leaves that have no chlorophyl. They turn green as the age.

I’ve never shown you how I get into the canyon. This is the view just as you come out of the canyon, looking toward the road, so we’re leaving rather than arriving. The ice climbers who come here kindly built boardwalks to get over the washouts that get bigger each year. You really have to watch your step through here because after the heavy rains of last summer the washouts have become deep enough in places to break a leg if you fell into one. When I’m moving through here I walk slowly and keep my eyes on the ground at all times. Just off to the left of that nearest boardwalk there is a washed out hole that could swallow a car.

There are seeps in this area as well, and this one had an iridescent sheen on it. Seeps are groundwater that lies on the surface like a huge puddle, but they never freeze no matter how cold it gets.

Looking forward, it will be nice to have the trail restored to its former condition with working drainage channels so it is not so muddy here, but for the next few months this will be a good place to stay away from.

It’s amazing how quickly nature consumes human places after we turn our backs on them. Life is a hungry thing. ~Scott Westerfeld

I hope everyone had a nice Thanksgiving Day. Thanks for stopping in.